Introduction

Urbanisation will be one of the key changes of the 21st century, as the worldwide urban population is expected to grow by 2.5 billion people over the next 30 years. These increased urban populations will require significant urban land expansion, which frequently comes at the expense of natural ecosystems. This poses a challenge for sustainable urban growth at a time when the world's biodiversity is gravely threatened.

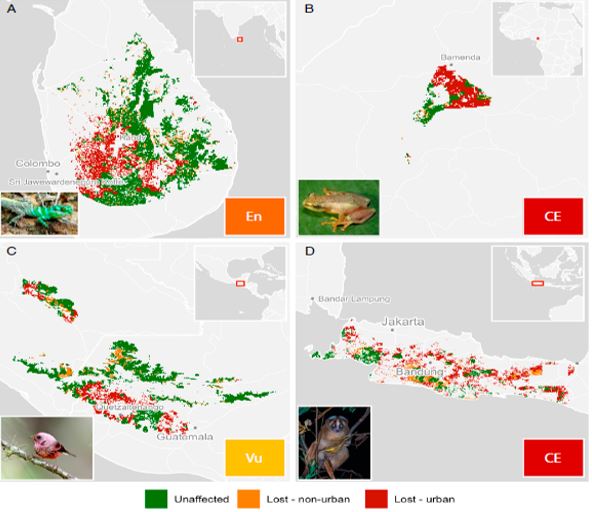

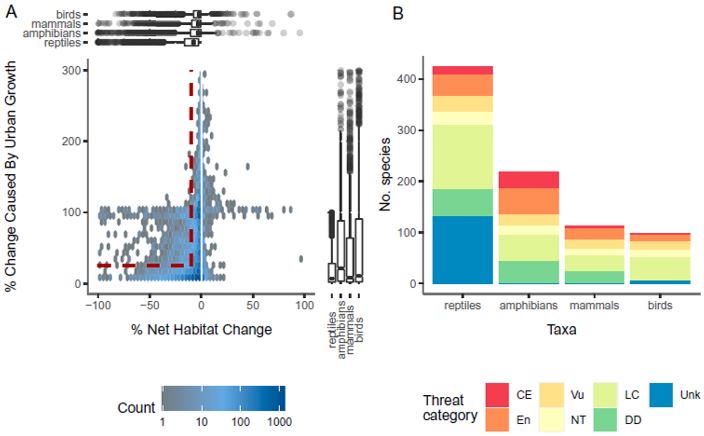

Plants and animals can live in cities, and most people agree that people need access to nature in order for cities to be useful and liveable for people. Yet, when urban land takes the place of natural habitat, it permanently changes the kinds of habitats that are available, as well as how they are arranged in space and how interconnected they are, which has a profound impact on the diversity and composition of species assemblages. The abundance of native species typically decreases as urban land use intensity increases. Invasive species are more common in urban settings, and their percentage often rises as cities become more urbanised. Moreover, urban terrain can promote phenotypic adaptations and hasten ecoevolutionary change. The reduction in global biodiversity is a result of these effects on the biota. For instance, between 1992 and 2000, habitat lost due to urban land growth amounted to over 190,000 km2, or 16% of all habitat loss during this time. Around 8% of the terrestrial vertebrate species included on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species are thought to be largely in danger as a result of urbanisation.

Even though urban land growth seems to be a big reason for habitat loss, there has been no global response to this problem. The Aichi Biodiversity Goals of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which are no longer in effect, and other international agreements to protect biodiversity have focused on the loss of habitat caused by agriculture and forestry. Still, by ignoring the growth of cities, a source of habitat loss that could be very important is being overlooked.

Understanding the size and location of these effects in the future is important for coming up with a social response to how cities affect biodiversity. Predictions of the effects of urbanisation on biodiversity can show how important urban land is as a cause of habitat loss.

By identifying particularly susceptible species or areas where impacts will be most concentrated, they may also offer insights that help with the implementation of targeted and effective interventions. 290,000 km2 of natural habitat will probably be lost to urban growth between 2000 and 2030, based on what is known about how cities are growing around the world.

This includes putting more than three times as much city land next to protected areas. It is expected that a lot of this urban growth will happen in places with a lot of different kinds of life, or "biodiversity hotspots." In 2000, many of these places had very little urban area. This is anticipated to cause losses in ecoregional endemic species, 13% of which are found in ecoregions where urbanisation is forecast to pose a serious danger.

Even though these analyses have shed light on how future urban land could affect biodiversity, they are limited in four important ways that make them less useful and less wide-ranging. To start, they have a coarse spatial resolution. It is challenging to identify the main players and their roles because they frequently discuss the effects of urban land at an aggregated scale (countries or bioregions) that may fall under the purview of several authorities tasked with biodiversity conservation. They also have poor taxonomic resolution.

They frequently make generalisations about species that might have diverse reactions to urban growth. Thirdly, they emphasise the effects of urban land without accounting for potential habitat loss outside of the metropolitan area.

For instance, combined habitat loss from urban and agricultural land growth may result in species extinction where these two land uses do not do so individually. Last but not least, current studies typically only anticipate implications out to 2030 or so.

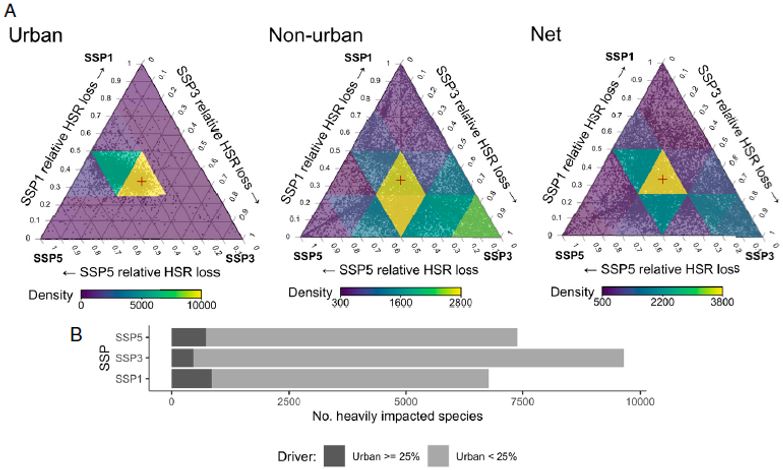

As this date draws closer, these forecasts lose their usefulness, necessitating the need for an updated set. We compare a scenario for sustainability (SSP1), a scenario for conflict between regions (SSP3), and a scenario for development based on fossil fuels (SSP5). SSP1 imagines a way to get to sustainable development where there isn't much population growth, less consumption, a lot of food from agriculture, and good regulation of how land is used.

©

©